| DISCOVERY GATE |

|

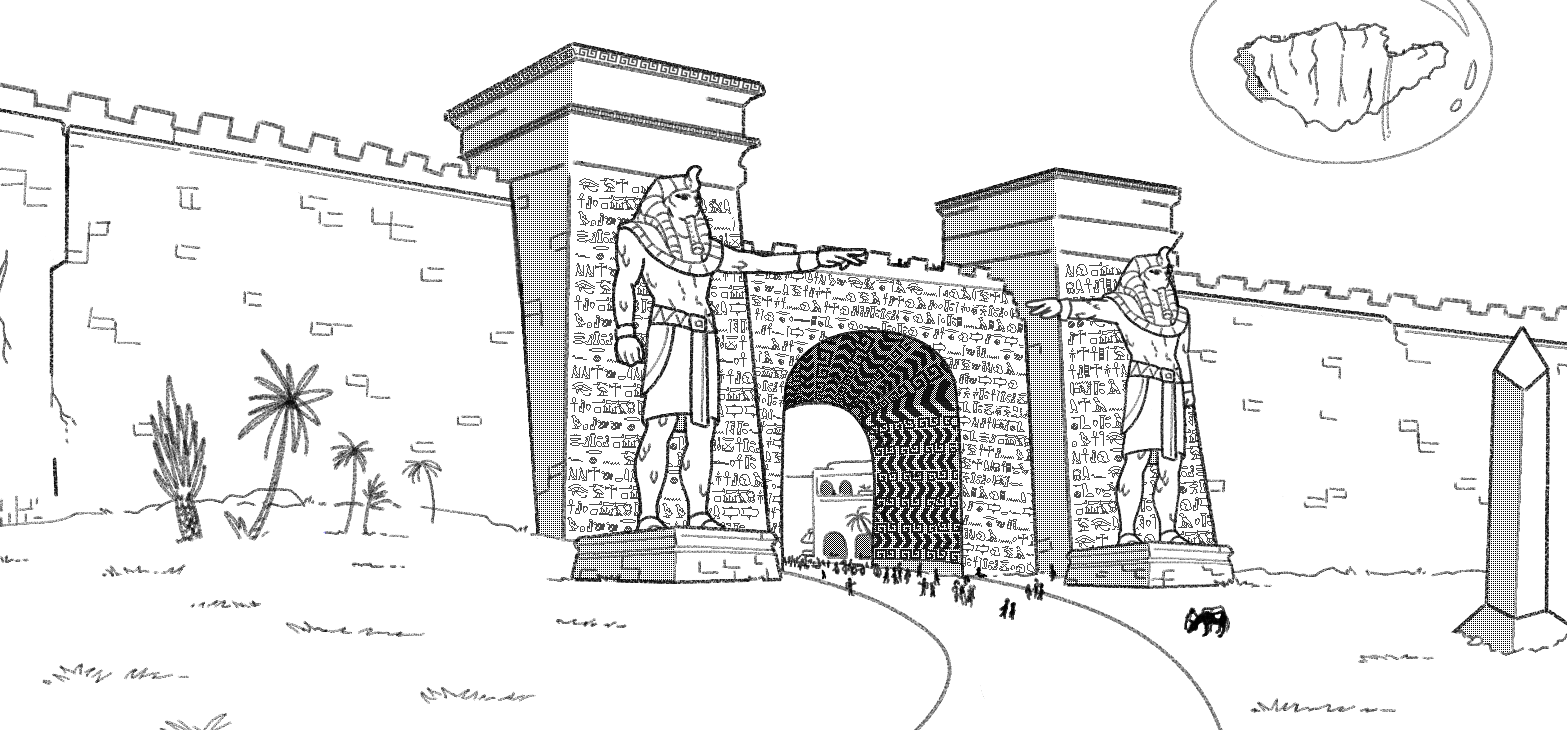

- Anecdotes of an Itinerant, Rinpoche Wong Tao  “Send me with her, then. You must keep your loyal sons close now.” Bogumila recognizes the wheedling tone in her stepmother’s voice. It’s a far cry from the venom the woman could spill and indeed Elzbieta makes no mention of the disloyal son. The conversation comes clearly through the hide curtain separating her bedchamber from her father’s. Bogumila curls in her bed under layers of furs, a pocket of feverish heat in the chill of the cave. She disentangles her horns from the blankets and pokes her head into the cool air, the better to hear. “And give them two hostages?” That’s her father, the mountain lord. He growls his frustration. “These travelers have me by the beard! They kill my… betrayer and swear to help Bogumila when all I’d offered them was threats!” He doesn’t name his treacherous son either. The girl can see his pacing shadow under the curtain. “They do not think like bandits.” There’s one of her stepmother’s barbs, naming her father and his gang for what they are. “All they want is peace for the lowlander village you torment.” With that rebuke sown she turns to reason. “The warrior among them is a man of his word. He will see us safe, and if he does not, I will sell my life for your daughter. Either of your loyal sons could do no better, isolated against them.” It’s true, the strange lowlander travelers proved themselves skilled fighters and powerful magi. They’d saved the mountain lord when Bogumila’s oldest brother raised his hand against his father. A shape moves in the darkened chamber. In the gloom she can make out a broad-shouldered form and tall horns and knows it’s him. The smell of blood and scorched flesh and hair fills her nostrils and she stifles a cough. Silence falls in the next room. The curtain is swept back and Bogumila is caught awake. Her father squeezes through the low passage and light streams in to fall on Borys where her dead brother stands. Blood flowing from his mortal wound stands out in richer ruby against his red skin. Killing spellfire left his face tattooed with black burns. Her father kneels by her bed, unable to see his son. The stump of one of his horns, broken by Borys’ blow from behind, is bandaged with a bloody cloth. His beard is matted and torn in grief. “Sleep, daughter,” his voice drops to a gruff whisper, “you will leave the mountain tomorrow.” Unseen, Borys looms over the vulnerable mountain lord as he did during his attempted patricide. “The travelers will take you to a great city in the lowlands, and find a healer for you. You’re rumiany: be strong, and you’ll return healthy.” Her father lays a huge hand on her head. Her stepmother holds the curtain aside, watching as well. Her shadowed face is unreadable. When Borys reaches out with maimed hands and wraps his fingers around his father’s throat, she says nothing. I’m dreaming, Bogumila realizes.  The rickety cart’s rattling broke through her dream and Bogumila sat up, shedding fur blankets and blinking in the bright sunlight. Her constant exhaustion and the rhythmic bump of the wheels on the road lulled her to sleep after the day’s travel began. A fortnight ago she’d left the mountain passes of her home and each step on the descent to the plains below tortured her with wheezing lungs, faltering steps, and febrile shivers. Someone tugged at the hem of her sarafan, and Bogumila saw it was the cart’s other passenger. Kasmut pointed wordlessly with her scaled hand and Bogumila followed the little girl’s silent gesture. Alongside the stone causeway the grassy plain was blanketed with white, as piercing to the eye as Father Cloud’s snow on mountaintops. It rippled as her eyes adjusted, revealed as bleached silk and canvas staked in tall walls around an encampment of equally bright tents. Tall cairns of balanced rocks reared above the cloth barricades with colorful wind-snapped streamers tied about them. From the causeway’s vantage, figures could be glimpsed moving within the curtain’s bounds, but never clearly. A wavering haze like heated air hung over the camp, full of drifting red motes. The entrance was a miniature labyrinth of canvas, guarded by two gangling warriors with spears even taller than themselves. “It’s the Cantonment, Kasmut, where the tylwyth live.” That was the mute girl’s older sister, who everyone called Princess. She was training to succeed her grandmother as priestess in the village below the mountain lord’s lair. Though of an age with Bogumila, she acted the know-it-all, an attitude emphasized by the supercilious tilt of her snubbed nose. “We’re not allowed to go in there. They’re like Eiiwen and Govannon: we can’t look at their faces.” Princess’ scales were parchment-colored like her sister’s, sometimes showing a sparkle of bronze. Bogumila’s father and brothers looked down on the villagers with contempt: the scaled iaret came to the mountains as conquerors ages ago, and now the lowlanders were starving farmers the color of the mud they lived in. The mention of the two tylwyth among the travelers sent Bogumila’s attention to them. Eiiwen skulked along behind the cart with her red hair loose under her hooded mantle. Her bloodshot eyes were all that was visible of her face; a length of dark cloth shrouded her mouth. She was fearsomely tall and spider-limbed to the girl’s eyes, with none of the proper bulk of a rumiany, and none of the womanly charm of her stepmother. The tylwyth was a worshiper of the Red and Blue Daughter, the goddess the lowlanders called Neath. Bogumila had seen Eiiwen hurl darts of the goddess’ fire far hotter than the little flames her own people could summon. Devotion like that was rare among Bogumila’s kind. The old tales taught that only the insane courted the attention of the gods. The other was as unalike Eiiwen as possible. Even taller, Govannon was armored like a real warrior, a loyal druzhynik of old tales, if a bit skinny. He towered over the old draft horse drawing the cart while he led it with a long-fingered hand. A steel helmet masked his face but for his sky-colored eyes, and she supposed he never took it off. She’d seen him tip it back just enough to eat before quickly lowering it again. Her stepmother walked alongside, sometimes with a hand on his arm, her skin soft blue against his dark patchwork garb. Elzbieta remarked something to him that Bogumila couldn’t hear, and smiled up at the man, seemingly pleased with herself. Shining bangles of gold hung from her broad horns and she’d worn her best dress and shawl despite the day spent traveling. Framing the pair, however, was a sight that stole Bogumila’s breath: a mountain range of sand-colored stone blocks that each dwarfed the distant people seen against them. The wall, for that is what it was, stretched east to west in the girl’s sight, anchored at either end against dark cliffs rising above the broad plain. The road entered a squared-off archway through it, crowded with more people than Bogumila had ever seen at once. “Discovery Gate!” Princess crowed, forgetting her usual prim composure. It was wide enough for four carts or more to pass through at once. Statues of ancient iaret explorers flanked the span, each with a graven arm outstretched and pointing south. A thousand years had weathered their squamous features, but their headdresses and panoply were newly-painted in blue and gold. Rising beyond the wall was the city with its mastabas of inky granite, alabaster-columned temple pediments, pointed red stone obelisks and steel towers glittering like sword blades. This was Keltokel, where the iaret built their colonial empire on ruins even more ancient. From the time she was born Bogumila had been surrounded by the Keizai Mountains’ cloud-wreathed peaks, but mortal hands built this. Mortal hands covered each stone with hieroglyphs and carved the visages of the Dynasts and explorers of old. And not the ozrut, her rumiany kin nor their markotny cousins, their craftsmanship hadn’t built this edifice. The iaret and armies of groaning workers had raised these stones, this city. How small she felt! Bogumila’s heart quailed, and the stink of ash choked her throat. She could feel eyes on her, measuring her weakness. Her eldest brother’s dying gasps stirred her tousled white hair in time with her own raspy breathing. “Help me!” she called out, first in her own tongue, but her stepmother didn’t notice through the hubbub of the busy road. The markotny just laughed prettily at something Govannon said, her kohl-lined eyes firmly on the gateway before them. Bogumila tried again in the lowlander language and was surprised when Eiiwen answered. “Blessed of Neath!” The shrouded woman regarded her with gimlet eyes. “The goddess of conflict offers you struggle! Come receive her favor.” One spidery hand was proffered to help the girl down from the moving cart. Bogumila stepped down and stumbled as her knees betrayed her. The tylwyth’s hand gave no strength, and the girl was left to pull herself back up. Once she was standing, Eiiwen released her. “More lively than your brother!” The older woman mocked her. “Perhaps you’ll be the mountain’s heir!” Beyond even her fevers, Bogumila’s red cheeks flushed with shame. “Be strong,” her father’s injunction came to her. She was rumiany, the daughter of the mountain lord! She hitched her fur shawl up around her shoulders and took a short, wobbling step after the cart. Kasmut clapped encouragement but the mute girl’s expression remained placid. Her slit-pupiled eyes flicked over Bogumila’s shoulder as if at someone standing there, but perhaps that was only her imagination. The presence behind her receded as she took another step, then another. “There you go, Bogumila!” That was another of the travelers, strolling alongside the cart with her thick tail swaying behind her. The young woman looked almost like a fish from the mountain lake above Bogumila’s home, right down to her long whiskers, but her scales were colored in gold, white and black instead of silver and no fish ever wore pink silks. Bogumila’s father had reason to distrust the woman at first: the piscine apkallu were long friends to the conquering iaret. However, Kasumi’s tongue was as golden as her scales, and her friendly manner impossible to deny. “Prayer wheels and sacred chants, temple bells and incense smells,” she hummed as she helped Bogumila reach the cart again so the girl could support herself on it, “in the city of cities, Keltokel, we’ll find a blessing for us as well!” Their progress now carried them beneath the gate and her tottering steps plunged her into the crowd there. Though Bogumila might stand as tall as her stepmother someday, now she was not quite so tall as a grown lowlander. The bodies of travelers surrounded her, cutting off her view. Only her grip on the greyed wooden flank of the cart kept her from being carried away. All the people! Iaret with flat, scaly faces and their chests sinuously bare in the spring day passed by, not even noticing the rumiany girl. Rivaling their numbers were humans with every shade of pink and tan to their skins. A kruk with shiny black feathers swaggered along in the opposite direction with a needle-like sword on his hip. The variety of dress dazzled Bogumila: high southern collars, turbans, white northern linens, quilted wool gambesons, even embroidered water silks from undersea realms. Aside from herself and her stepmother, however, there were no ozrut, red or blue no matter how she searched. Like the busy crowd, the world went on without them while they secreted themselves in deep forests and high mountains. The cart stopped, blocked by another laden wagon. The teamster atop the wagon clacked his curved beak and trilled an imprecation at a slow-moving gaggle of robed iaret ahead of him. The procession of priests shuffled under the weight of the spinning mantra mills they carried. Combining the words on the rotating wheels with their sonorous chants formed an ever changing prayer. Bogumila took advantage of the merciful pause and leaned against the gate’s interior wall, exhausted. Hundreds of tiles, cool to her touch, lined its surface. Their glaze was chipped and left gaps in the long geometric designs. Her nearness startled a nest of nudiflots in a gap between broken tiles and they burst forth with a sudden fluttering of gauzy wings. One of the colorful gastropods alighted on her arm and its eyestalks extended, regarding her. Bogumila stared back. The air was too cold and thin for them in her mountain home. Slowly, she lifted her arm to get a closer look. That movement saved it. A wet black shape leapt for the nudiflot with gnashing needle fangs and raggedy, dripping fins but the little slug unfurled its wings and flapped away in a panic. The anglerfish plopped back into its water-filled lantern floating in midair nearby. Its glowing lure bobbled grotesquely as it thrust its maw back above the water. “You made me miss, you little bedrel!” it accused her in a gurgling voice. “Be kind, Fishbones.” The last of Bogumila’s escort collected the wayward familiar’s levitating bowl. Her skin was paler than most humans and painted with ink in shocking contrast. The other travelers called Lamina a witch and the girl was inclined to believe them. Who else would keep such a nasty little fiend as a fetch? The witch’s lips curved in one of her seductive smiles when she turned to Bogumila. In that, however, the rumiany girl knew her sort. The shapely human and her stepmother shared those more mundane arts. “Don’t get left behind, dear.” The drover ahead had bulled his way forward and their own cart was moving again. Passing from under the shadow of the gate, Bogumila could see the main thoroughfare, paved in gold-colored flagstones, winding through the city and down to the sea like a great serpent. Towers, temples, and buildings she had no word for crowded around a maze of lesser streets. Between the stumps of sunken ruins in the bay, ships with bellied sails scudded along bound for or returning from lands she couldn’t even imagine. Above them a great heap of earth, an entire hillside studded with sprawling manors, was suspended from the sky in what looked like nothing so much as a soap bubble. She turned away, numb from the unbelievable sight. For all her surviving brothers’ brigand boasting they could not have brought her here let alone kidnapped a healer for her. It took the strange lowlanders to navigate this otherworldly place. The travelers would find help for her, or they would not. They would return her home as they swore, and they would depart. Her stepmother, having slipped from under her father’s thumb, might leave with them. Princess and her sister would study the teachings of the gods at the city’s grand temples. But where was Bogumila’s place in this world? What was her future? Gazing back toward the south, she glimpsed a tall, horned figure standing amidst the unheeding throng. Blood slicked her eldest brother's red skin and his proud shock of white hair was burnt to stinking tufts. He glowered at her with dead, sightless eyes. “Rejoice!” Eiiwen cried suddenly, “the mountain heir is dead!” Bogumila tore her eyes away from the apparition and stared at the holy madwoman in shock. “You have left behind that Bogumila! She is gone. Only you remain. Long live the mountain heir!” The woman’s mask twitched with her proclamation. Was she smiling beneath it? “Now I shall really make you think,” she leaned down from her unnatural height to whisper to the girl, “you, that Bogumila, and the healthy and hale girl still to come are one and the same.” The tylwyth’s chuckle had a tinge of hysteria to it as she straightened and strode onward into Keltokel. A hundred temple bells ringing the hour throughout the city of cities vibrated Bogumila’s thin chest. She turned away from the gate and took the first step on that gilt road. Pungent incense drifting on salt breezes dispelled the scent of ashes. |